State Action on Bolstering Clean Water Act Protections

What’s the Issue?

Federal jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act (CWA) is limited to “Waters of the United States,” or WOTUS for short. WOTUS defines where the federal government can require permits to protect rivers, wetlands, lakes, estuaries, and other waterbodies from pollution. In the 21st century, this definition has undergone a series of alterations by courts and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In 2001 the Supreme Court ruled that federal jurisdiction did not extend to isolated intrastate waters, invalidating the existing definition of WOTUS used by the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers. Five years later, the Supreme Court, in a case called Rapanos v. United States, decided that traditionally navigable waters and interstate waters with a “significant nexus” to such waters were subject to CWA jurisdiction. In 2015, the EPA issued a new regulatory definition, expanding the definition of WOTUS and extending federal protections. This expansion included numerous wetlands and headwater streams that had previously been excluded, despite their importance to the water quality of the larger waterbodies they flow into.

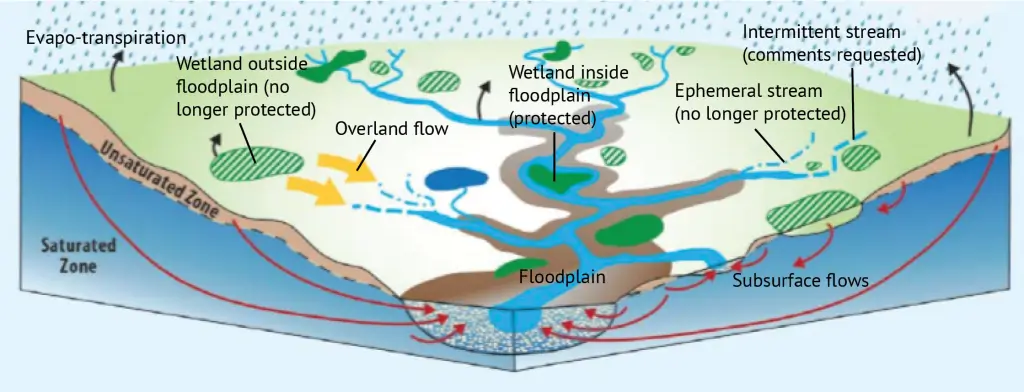

Image of hydrologic connections and protections under the Clean Water Act from American Fisheries Society, adapted from a US EPA 2015 graphic.

This new definition was yet again challenged in federal courts, and was eventually replaced in 2020, with a new rule based on Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion in Rapanos. This rule removed federal protection from wetlands, headwater streams, and ephemeral streams, all of which can have major impacts on the water quality of larger, unquestionably jurisdictional streams. As a result, this “Navigable Waters Protection Rule” (NWPR) became known as the “Dirty Water Rule.”

In 2021, EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers withdrew the Dirty Water Rule and released a revised definition of WOTUS rule at the end of 2022. This revised definition has since come under attack through court rulings.

In May 2023, when ruling in the Sackett v. EPA case, the Supreme Court catastrophically narrowed the scope of the Clean Water Act by drastically reducing wetland protections. On September 8, 2023, EPA published a final rule amending the revised definition to conform to the Court’s decision. Visit our Waters of the US resource page to learn more about WOTUS and our blog post about the impact of the Sackett v. EPA decision.

In light of these rollbacks, some states are stepping up and clarifying what streams are protected from unpermitted pollution under their own laws or expanding their state jurisdiction to make sure critical headwater streams are protected.

Examples of State Policy & Regulations

Lawyers for Good Government’s Wetlands Dashboard provides information on state level water and wetland protections for all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Information for each state includes definitions of “waters of the state” and “wetlands;” relevant regulating agencies protecting these resources; protections for wetlands that already exist in the state; any proposed changes made to wetlands protections as of May 2024; processes for amending existing state law and policy defining state water and wetlands; protections potentially available at the local level, and; if the state offers a model policy for protecting wetlands.

Chantel Dominguez, Community Campaigns and Engagement Director with American Rivers shares state-level water policy strategies through the lens of American Rivers’ Most Endangered Rivers 2024. The rivers of New Mexico (yes, all of them!) topped the list, as Sackett left virtually all of the state’s streams and wetlands vulnerable to pollution.

Additional Resources

- Sackett v. EPA: The State of Our Waters One Year Later from Protect Clean Water campaign

- State-level analysis of Wetlands and Streams Most in Danger After the U.S. Supreme Court’s Sackett v. EPA Ruling

- Clean Water for All Coalition Report: Sackett v. EPA: The State of Our Waters One Year Later (May 2024)

- Earthjustice State-level analysis of Wetlands and Streams Most in Danger After the U.S. Supreme Court’s Sackett v. EPA Ruling

- Environmental Law Institute’s analysis of states’ ability to fill in regulatory gaps in water protection, Murky Waters Ahead? State Protections for Nonfederal Waters (2022), James McElfish

- EPA supplementary materials published in preparation for the repeal of the Dirty Water Rule includes a list of state actions on jurisdiction after NWPR

- River Network’s Waters of the United States (WOTUS) page tracks the current definition of WOTUS and features relevant news stories

- Clean Water Act Owner’s Manual

- Clean Water Act Training Series – Module 5: Protecting Wetlands, Streams, and Lakes from Dredging and Filling ‐ Section 404

- EPA’s About Waters of the United States webpage

- EPA’s Current Implementation of Waters of the United States webpage

- Harvard’s Environmental and Energy Law Project has a timeline of the controversy over federal jurisdiction

- Earthjustice story map explores the implications of WOTUS’ moving definition

- Redefining Waters of the United States (WOTUS): Recent Developments, Congressional Research Service, July 8, 2022

- The Status and Trends of Wetland Loss and Legal Protection in North Carolina, North Carolina State Extension Publications, 2022

- Trout Unlimited interactive map on the importance of intermittent and ephemeral streams

- Report: The contribution of headwater streams to biodiversity in river networks Research from the U.S. Forest Service shows that headwater streams are critical to biodiversity. Judy Meyer, U.S. Forest Service, et al.

- Report: The Role of Headwater Streams in Downstream Water Quality Research from National Institutes of Health found that protecting headwater streams positively impacts downstream water quality. Richard B. Alexander, USGS, et al.

Development of the State Policy Approaches to Bolstering Clean Water Act Protections State Policy Hub category was led by Charles Miller.

Bolstering CWA Protections Policy Database

| Name | State | Action Agency | Policy Focus | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Rulemaking: Critical Area General Rules, D.C. Mun. Regs tit.21, § 2500-2505, 2599 | Washington DC | DOEE (Department of Energy and the Environment) | Clarified that wetlands which had been removed from Waters of the United States (WOTUS) protection were still subject to 401 permitting under DOEE regulations. |

|

| Ordinary High Water Mark legislation (Miss. H.B. 594 (2021)) | Mississippi | Department of Marine Resources | Provided a definition for "Ordinary High Water Mark," a previously undefined term that set the boundaries for coastal wetlands. Not an "expansion" of jurisdiction per se, but admirable step to ensure jurisdictional determinations have a scientific basis. |

|

| Wetland Rule Change: 15A NCAC 02H 0.1400 et seq.; 15A NCAC 02H 0.1301 | North Carolina | Environmental Management Commission | Like the Ohio rule, this rule filled a gap in permitting. NWPR left a category of wetlands in NC under the state's jurisdiction, but without state or federal permitting requirements. This rulemaking established permits for these wetlands. |

|

| State of Ohio Isolated Wetland and Ephemeral Stream General Permit | Ohio | Ohio EPA | Created a general permit for wetlands and ephemeral streams no longer covered by the federal Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR). |

|

| Memorandum to Environmental Quality Commission (Interpretive ruling) | Oregon | Department of Environmental Quality | Clarified that Oregon still intended to enforce its waters of the state jurisdiction, notwithstanding changes to WOTUS. |

|

| Rules and Regulations Governing the Administration and Enforcement of the Freshwater Wetlands Act, 250 R.I. Code R. 150-15-3 | Rhode Island | Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, RI Coastal ResourcesManagement Council (CRMC) | Required establishment of wetland buffers and setbacks, phased out local rules which would conflict with new state regulations. The rulemaking was influenced by the findings and recommendations of a Legislative Task Force (LTF) previously established by the Regulatory Reform Act. |

|

| An act relating to Vermont standards for issuing a Clean WaterAct section 401 certification, VT HB 108 (2021); 10 V.S.A. § 1253 | Vermont | Agency of Natural Resources | Not strictly jurisdictional, but expanded protections under the state's 401 program by ensuring that 401 certification could only be issued in circumstances where there is "no practicable alternative that would have a less adverse impact on wetlands and waters of the state." The bill requires that the State conduct a cumulative impacts analysis of the water quality impacts on waters and wetlands of an activity subject to the CWA section 401 certification. |