State Action on Water System Regionalization and Consolidation

What’s the Issue?

There are more than 50,000 community water systems in the United States, and of these, 8% serve more than 246 million or 82%, of the total population. In contrast, there are around 15,000 publicly owned treatment works in the country. Drinking water systems, particularly smaller systems with limited resources, often lack what the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) describes as “technical, managerial, or financial” (TMF) capacity. State-level approaches to address TMF issues include a variety of mechanisms to enhance utility partnerships, including consolidation and regionalization.

Consolidation and regionalization of water systems can be a highly contentious subject. In some parts of the country, such as California, forced consolidation has been praised as a way to bring clean, safe water to communities previously unable to access it in their homes. In a report from US Water Alliance and DigDeep, they assert that consolidation “should only be pursued if it will lead to better outcomes for all communities involved” and “policymakers should be aware of power dynamics and ensure that all stakeholders have a voice in negotiations.”

Consolidation and regionalization enable water and wastewater systems to operate at appropriate economies of scale. Water systems must continue to meet regulations while simultaneously facing increasing infrastructure costs. Restructuring enables underserved, smaller systems to maintain affordable rates, ensure compliance with drinking water standards, and in some cases, connect unincorporated communities to water systems for the first time. Large water systems can also benefit by expanding their rate-payer base, increasing operational efficiency, and reducing costs through joint buying power.

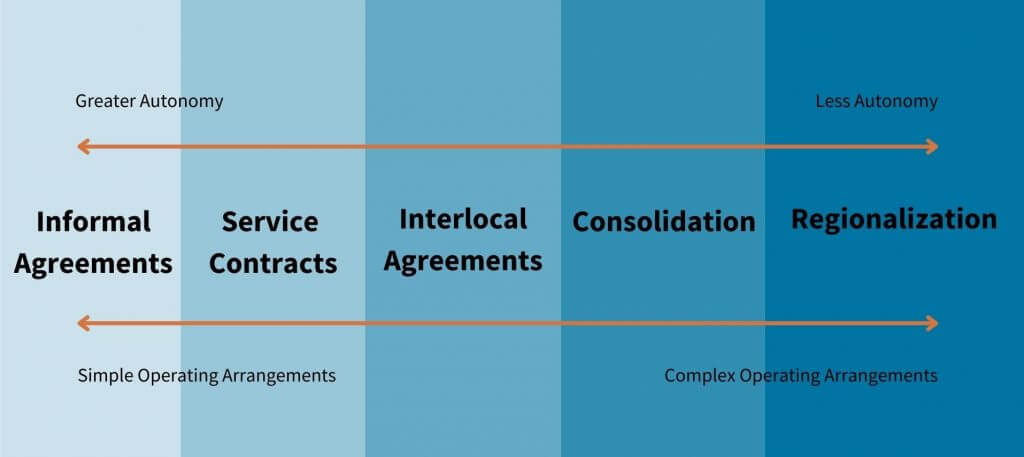

As defined by the US Water Alliance, “Consolidation occurs when two or more legal entities become one operating under the same governance, management, and financial functions.” Regionalization can include the physical interconnection or consolidation of two or more systems, or may focus on administrative solutions such as cooperative purchasing and contract operations or billing.

According to a compendium developed by the EPA on state water system partnerships in 2017, 35 states offer priority points in their Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) for partnerships, and 10 states encourage water system partnerships through specific grant programming (to learn more about the SRF programs, see our SRF Advocacy Toolkit. Fourteen states require new systems to consider interconnection to existing systems, and some states, such as California, now have the authority to force consolidation under certain circumstances.

Image adapted from Metropolitan Planning Council, The missing component in water service regionalization debates: equity

Examples of State Policy

- North Carolina: In 2013 the State Water Infrastructure Authority was established to develop a state water infrastructure master plan and to award funding for infrastructure projects. In 2015, House Bill 97 established Merger/Regionalization Feasibility Grants to study consolidation feasibility. The Authority prioritizes communities with smaller populations that are comparatively worse off across state benchmarks for economic indicators, and whose monthly utility rates are higher than the state median. The Viable Utility Reserve was established through House Bill 1087 in 2020, providing grant funding for local government units and to provide a statutory process for merger and dissolution of water and wastewater systems. Grants can be used for physical interconnections and extensions to regionalize water service, rehabilitate existing infrastructure, or to decentralize water systems into smaller viable parts if more appropriate. There are nearly 2,000 community water systems in North Carolina.

- Kentucky: Senate Bill 409, passed in 2000, created a planning process for water systems across the state to regionalize and bring potable water to more residents. Area Water Management Councils were created in each of Kentucky’s 15 Area Development Districts (ADDs). The Councils meet to discuss infrastructure needs and planning, and submit their reports to the Water Resources Information System (WRIS). Kentucky Infrastructure Authority (KIA) uses the WRIS information to prioritize funding from the DWSRF. An amendment to Kentucky Revised Statutes in 2008 gave the Kentucky Public Service Commission (PSC) the authority to study the feasibility of merging water districts. The PSC may order the merging of water districts or associations after holding public hearings, and may make other orders related to rates and charges. Since the 1970s, Kentucky has gone from over 3,000 public water systems to less than 500.

- California: Senate Bill 88 (2015), Senate Bill 552 (2016) and Assembly Bill 508 (2019) all enhance consolidation efforts in the state. SB 88 authorized the State Water Resources Control Board to incentivize and mandate physical or operational consolidation of failing water systems. SB 552 allows the Board to order an extension of service to an area that does not have access to an adequate supply of safe drinking water as a step towards consolidation. AB 508 amended the California Health and Safety Code’s provision that authorizes consolidation or extension of service if a disadvantaged community is reliant on a domestic well to instead authorize consolidation or extension of service if a disadvantaged community, in whole or in part, is substantially reliant on domestic wells that consistently fail to provide an adequate supply of safe drinking water. In 2023, the state celebrated 100 water system consolidations since 2019. According to the State Water Resources Control Board, California has 7,500 public water systems, of which approximately 92 percent serve fewer than 1,000 connections.

Additional Resources

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Building the capacity of drinking water systems -Kentucky.

- Rural Matters. The road to regionalization: Small systems find collaboration as one solution for addressing issues. (2009)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Water system partnerships: State programs and policies supporting cooperative approaches for drinking water systems. (2017)

- US Water Alliance. One Water Big Idea: Advance regional collaboration on water management. (2018)

- US Water Alliance. State Policy Makers Toolkit. (2019)

- US Water Alliance and UNC Environmental Finance Center. Strengthening utilities through consolidation: The financial impact. (2019)