AI is a Risk to Water. Here’s How Network Leaders are Responding.

This piece was cowritten by Jenny Tompkins, River Programs Associate.

You’ve likely heard a lot about AI over the last year. We have, too. From EPA’s new pillar focused on United States AI leadership, to seemingly every app and company recommending their own AI-driven tools, artificial intelligence is all over the place. The rapid expansion of AI will require vastly more data centers across the United States, and expansion of existing centers.

But where are data centers being built, and what does this have to do with water?

The answers are, unfortunately, everywhere and a ton.

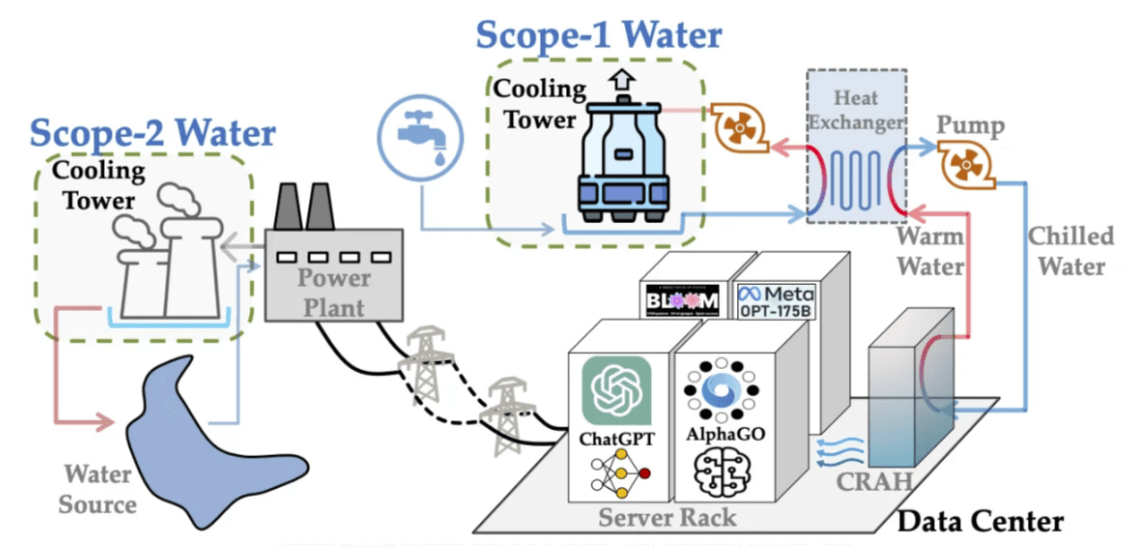

Data centers require a great deal of water for cooling, and the water discharged from that cooling is altered in chemical composition and temperature, affecting water quality, wildlife, and plant life. Then, there are the energy needs – primarily met by fossil fuels – to power these facilities.

These impacts have been on water advocates’ radar for years, but even more so today as energy usage ramps up as a result of AI. We talked to some advocates across the network to try to understand how AI is ramping up concerns about data centers in water-scarce regions and how people can mobilize around this issue.

“We have the data,” says Jonathan Gilmour at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “but it is aggregated across the US. This allows companies to hide extreme water usage in water-stressed areas.” Regardless of where you live, writing one email with ChatGPT search uses 16.9 oz of water, about the size of a standard sized Nalgene water bottle. Generating an image uses significantly more. By 2027, global AI water demand is projected to account for 30–47 million people’s yearly water consumption (about the population of Canada).

Many organizations are calling for their state to pause data center development due to a lack of research and data transparency from individual industrial users. Nationwide, there is a concerning lack of data for this kind of water usage, and water leaders are calling for accountability.

“Everybody’s trying to learn more about data centers,” says Jennifer Walker at Texas Living Waters. Central Texas is one of those regions facing significant water challenges due to rapid growth. Data centers have always been a major industrial water user, but AI has exacerbated the issue within the last year. “They’re coming on so fast. Even our state water plan through the Development Board, which is pretty comprehensive, is trying to get information about data centers and how much water they use. It’s a big unknown.”

Similarly, KD Minor at The Alliance for Affordable Energy is pushing for accountability from Meta, who is working toward building a fossil fuel powered data center in Richland Parish, Louisiana. “Essentially, we were just asking them to show their work. We’re not being difficult. We just want to know how you got to three gas [power] plants. Why not two? Why not solar? We are the only organization within the state who is challenging any of this.” Experts at the Alliance have had to sign multiple confidentiality agreements in order to access the most basic information.

Jonathan Gilmour says this problem stretches beyond Texas and Louisiana. “Meta, which has a data center in Eagle Mountain, [Colorado], has an agreement in which the city must notify [Meta] of requests for water use data. That the company has the right to contest requests as sharing ‘Confidential Business Information.’ In other words, Meta has a say in who gets to see its records. This lack of transparency is deeply problematic given the sheer volume of water data centers are using.”

The power of partnerships and coalitions cannot be understated here. The Alliance for Affordable Energy partnered with the Union of Concerned Scientists to understand where and how they could apply pressure. “We started our approach by asking questions,” says Emma Meyerkopf. “We want to get folks thinking about the water usage, the surrounding communities, and what happens after that Meta contract expires.”

An additional challenge is that many residents see this development as an economic boon. Meta in their neighborhood means more jobs, more opportunity. The reality that the Alliance is working to impress upon residents is the unlikelihood that these jobs would be filled locally, and that this development would come at significant cost to their health and access to clean water. Perfect Union recently reported from Mansfield, Georgia, on what happens once a Meta data center is in place. The resulting impacts on water quality and quantity is catastrophic.

“Louisiana has no body that appropriates our water,” KD reminds us. “It leaves the question of where [Meta] is actually going to withdraw their water? This facility is going to sit on an aquifer recharge area. So, the assumption is that they’re going to be drawing water from the aquifer, or from water that will never make it to the aquifer. How, then, will it replenish?”

For these reasons, water advocates are saying no to AI, at work and in their personal lives. But there’s something about the fact that every time I search Google, I am given an automated AI response. When I log into Zoom, I am given the option to generate an AI transcript. These tools are ever-present and tempting in their convenience. In this way, AI mirrors into the broader climate challenge: solutions are both systemic and closer to home.

You can contact your local, state, and federal officials to share your concerns about data center expansion. “We’re finding that elected officials don’t know what they don’t know when it comes to data centers,” says KD Minor. “Educating them and bringing them along, while reminding them that they have a responsibility to oversee this thing and make sure that everyone is being accounted for, is essential.”

The data transparency challenge is real, but do we know enough to say that unchecked development of fossil fuel-powered data centers is too great a burden for our climate, communities, and water. “Do cities have the ability to say ‘no, thank you’ when data centers come in?” Jennifer Walker asks. “We don’t know. These are the types of questions people are just now answering.”

This is one of the best essays I’ve read about AI / Water. I’ll be sharing it with others. Thanks!

Just read an article by Stephen Starr for Great Lakes Now on data centers and the Great Lakes — definitely a lack of information and transparency on data center water use and high concerns re: water impacts. https://www.greatlakesnow.org/2025/05/are-data-centers-a-threat-to-great-lakes/