Listening to the Echoes: Two Decades of Clean Water Act Training

In 2018, I was sitting in a Clean Water Act workshop session at River Rally in Olympic Valley, CA, led by Judy Petersen, Executive Director of Kentucky Waterways Alliance (KWA). Judy and I have worked together for many years, and not very far into the session, I recognized the slides she was using: they were adapted from the materials River Network developed and has used for decades to train individuals on the tools and power of the Clean Water Act (CWA). I began to reflect on the many other echoes of our CWA training work. How many people have we trained? How many of them are now training others? What impact has this had on the watersheds across our country?

Lynn Camp Creek, Green River Basin, Kentucky. Natural large karst spring-fed cold water creek protected through local organizing by Kentucky Waterways Alliance. Photo by Judy Petersen.

Judy’s use of the CWA in Kentucky took on many forms. In one memorable public meeting, she orchestrated a roomful of fishermen and property owners telling their stories of catching trout in rivers across state, not only when they were young, but to this day. Their stories illustrated the dependence of the state’s most sensitive fish species on particular Kentucky rivers, and they contradicted the state’s plans to reduce protections in dozens of those waters. KWA succeeded in maintaining protections on many of those streams because of the fishermen’s voices.

Stories such as this one have reinforced the value of citizen engagement and advocacy in the implementation of the Clean Water Act…especially now…when state programs are strapped for funding and federal oversight is severely limited.

Our work disseminating CWA tools has taken on many forms and supported the protection and restoration of watersheds across the country, reverberating throughout our national network of local water protectors. Here are just some of the ways.

Strengthening the Voice of Tribal Authority

River Network worked with the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council and Cook Inletkeeper to convene tribal leaders coming from all parts of Alaska in 2001 and 2002. In these convenings, we and other experts discussed the Clean Water Act and its relevance to sovereign tribal nations in Alaska. River Network facilitated strategic thinking about the legal tools to protect the waters the tribes care about most. This work launched many more years of work with tribes all across the United States including Picuris, Taos, and Sandia Pueblos in New Mexico, the Penobscot Nation in Maine, and the Navaho and Northern Arapahoe Tribes in the establishment of the Indigenous Waters Network.

Rio Pueblo de Taos, New Mexico. River Network worked with Taos Pueblo Environment Department staff on instream monitoring and Clean Water Act protections. Photo by John Phelan (CC BY 3.0).

All of these tribes looked for ways to protect and institutionalize their values around and uses of water. Some of them had the “blessing” of the EPA to develop their own water quality standards, and it was important to look for strategies beyond that “blessing.”[1]

Protecting Spiritually Important Drinking Water Sources

In New Mexico, a broad coalition of groups including ranchers, local businesses, hunting guides, municipalities, and conservation groups came together in 2005 to protect a treasured area called the Valle Vidal using guidelines from River Network’s Clean Water Act course.

Comanche Point, Valle Vidal. Sacred waters protected through New Mexico’s Outstanding National Resource Waters designation. Photo by Jim O’Donnell.

The coalition, which focused on antidegradation in addition to other issues, was organized and supported by Amigos Bravos, the statewide organization protecting rivers in New Mexico. Rachel Conn, Projects Director at Amigos Bravos, was among a group trained as CWA trainers by River Network in 2003. Says Rachel, “through this training, I really got my feet wet with the CWA and have implemented a lot of projects following these tactics. I was also able to train others in New Mexico. The technical skills River Network provided through the Clean Water Act Course gave us tools we have used as a statewide organization. I still hand out the Clean Water Act Owner’s Manual to new employees and interns on their first day!” Among many other successes, Rachel and Amigos Bravos led the charge (with River Network’s help) that resulted in New Mexico adopting the steps for nominating (20.6.4.9 NMAC, p. 8) and the requirements (20.6.4.8 NMAC, p. 6) for protecting the state’s most outstanding waters under the antidegradation policy. These new regulations opened the door for the Valle Vidal nomination and ultimate protection.

Read more about Rachel and Amigos Bravos.

Working Locally, Sharing Nationally

Throughout the years of CWA trainings, policy analysis, and 1-on-1 support, River Network has always been able to share local examples with other local, regional, or national audiences through River Rally, River Voices, and each subsequent training and consultation. Our focus on continuous learning, packaging, and dissemination has been the backbone of our organization and has fueled the “echoes.” We are self-described “Johnny Appleseeds” of great ideas that might otherwise stay in one region or locality. In one notable example, Prairie Rivers Network developed an Illinois-focused guide to reviewing CWA pollution permits. River Network partnered with Prairie Rivers Network and Clean Water Network to develop a national version called Permitting an End to Pollution that can still be used to review pollution permits in any US state today.

Strengthening Knowledge on Specific Issues and Tools

Local groups became more aware of the devastating and ubiquitous impacts of stormwater pollution and erosive, flashy flows during the 2000s. At the same time, River Network developed an expertise on the various components of the CWA stormwater permit programs. In Alabama, a coalition of watershed organizations led by Cahaba River Society and Mobile Baykeeper (Alabama Stormwater Partnership) formed to learn more about the existing stormwater permits, highlight the shortcomings of the state and local stormwater programs, and combine advocacy forces to improve the permits and practices throughout the state. River Network supported this effort through trainings, policy and permit analysis, and advocacy support. Over this time, the coordinated pressure on the state and local jurisdictions resulted in improved permits and practices.

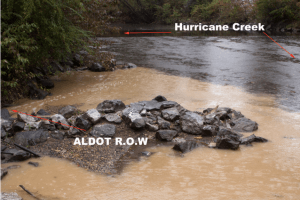

Hurricane Creek, Alabama. Impacts of poor practices during road construction by Alabama Department of Transportation. Photo by John Wathen, Hurricane Creekkeeper.

Building Relationships That Last

In the Southeast, River Network convened directors and policy staff from all the major state-based watershed organizations several times to discuss the differences of CWA implementation and enforcement. River Network also invited the state and regional EPA water quality staff to participate in order to make acquaintances, develop better understanding of each other’s perspectives and objectives and build valuable relationships. The communication and coordination on CWA strategies across the southeastern states has been strong for many years and continues today on streamflow policies and strategies.

Read more about our current Southeast work and hear from Matt Rota, a former CWA “trainee” in Louisiana who continues to share his CWA knowledge with others.

With change comes reflection. This work is far from finished. Though my time as part of the River Network staff is drawing to a close, my work with the community will continue. There are always new people joining our watershed movement, and there is always a need for new strategies to tackle the present-day threats to our waters. Now, more than ever, we are in need of an informed, engaged, and powerful community of advocates. I hope to see further echoes of our CWA work in the coming decades, with more trainers like Judy, Matt, and Rachel, and even more advocates from populations who were previously absent from these settings and who now have the confidence, knowledge, and tools to stand up for the waters and communities they care about most.

[1] To administer a WQS program under the CWA, a tribe must apply to EPA for authorization to be treated in a similar manner as a state.

This is very empowering and an eye opener to convey this kind of knowledge and information about the protection and preservation of the water resources to tribal communities. My country South Africa is predominantly tribal land and water for drinking and productive livelihoods is a key commodity. Quality and availability of this resource is becoming a national challenge that requires mitigation strategies at all levels of governance. Stewardship remains the unifying and core approach for collective decision making and preservation of this scarce resource.

Gayle, I don’t think you’ll ever truly know the impact that the CWA toolkit and trainings have left on the thousands of citizens (professional and volunteer) who have taken a training, used the toolkit. Knowing that water belongs to us, and it’s our role to defend it, is incredibly empowering.

Gayle – We all owe you a debt of gratitude for your dedication to the cause of clean water and commitment to our community of advocates. Thank you!!

Gayle,

Next to the phrase, “citizen advocacy for our waterways“ in the dictionary, there is a picture of Gayle Killam. You have been the heart and the soul of this work for two decades. It has been an honor to work with you, learn from you, and most importantly, to call you friend. Best wishes as you embark on this next phase of your water advocacy journey.

Much love,

Todd